Updated: December 29, 2009, 12:11 PM ET

For Harwell, there is still much to doBy Elizabeth Merrill

ESPN.com

NOVI, Mich. -- A sign outside Ernie Harwell's apartment door politely asks would-be visitors, in so many words, to give an old man and his wife some peace and quiet. Ernie didn't hang it himself; he's far too nice for that. When times were better and cancer wasn't invading his body, Harwell tried to answer just about every card and letter. Now he has 10,000 of them piling up, along with a freezer full of casseroles and cookies and other good intentions.

It's a cold, gray December day on the outskirts of Detroit, and Harwell has taken a late-morning nap to gather his strength. There is so much to do. Dodgers broadcaster Vin Scully's people called. They want to give Harwell, the beloved voice of the Detroit Tigers for 42 years, a lifetime achievement award. There's a stack of e-mails to go through, a one-man play based on his life to finish, guests to entertain. Today, two well-dressed TV personalities have stopped by to give him a 5-foot-wide card covered in signatures. Ernie, thanks for responding to the letter I wrote you in third grade. Made the summer of 1987 awesome to me. Harwell smiles at that one.

The TV folks say their goodbyes, and one of the men shakes Harwell's hand and says he'll see him on Opening Day.

"I hope so," Harwell says.

He closes the door. He knows he probably won't be around by then.

How do you say goodbye to Ernie Harwell? Jose Feliciano sent a massive bouquet and a note signed with love, then sent another bunch of flowers four days later. The devout women of the Ames United Methodist Church in Saginaw, Mich., knitted a shawl and prayed over it. Harwell is dying, which means the childhoods of roughly four generations are dying.

And all of them seem a lot more troubled by it than Harwell is.

The agentGary Spicer doesn't stop to think about what life will be like without Harwell. Spicer eats a bowl of clam chowder at a restaurant he often frequents, and asks the waitress who's the greatest celebrity she's ever met. That's easy, she says. Ernie Harwell.

Spicer has been Harwell's lawyer, agent and friend for 31 years but has the energy of a pit bull puppy. He has tousled gray hair and a cell phone constantly dangling from his ear. He orders a spinach salad but can stay only long enough to eat half of it. Between bites he gives an update on Harwell's condition: Ernie had a bad infection and jaundice last month but rallied. He's lost about 15 pounds and may be slightly self-conscious about it. But he was never a big man anyway, Spicer says.

The state of Michigan knows most of the backstory that brought them here, to the end. Back in August, doctors gathered in Harwell's apartment with Lulu, his wife of 68 years, next to him and delivered the grim news. Cancer of the bile duct. Essentially inoperable. They could do surgery, but the percentage of success was low and the risk was high. One of the doctors told Harwell that if he were his father, he'd just tell him to relax, let things happen and enjoy himself as much as he could until the inevitable.

So Harwell waits, for a month, maybe more, until the inevitable. He tells Spicer that he's at peace. He's 91 years old, surrendered himself to Jesus nearly 50 years ago at a Billy Graham crusade and has seen just about everything. The first inning of his first game behind the microphone, he watched Jackie Robinson steal home. He still believes Willie Mays was the best ballplayer he's ever seen. He still knows baseball is the most perfect game because of its continuity.

Harwell's blue eyes still twinkle, and his easy, Southern voice never crackles, leading friends to hope that mettle will win out over medicine. Harwell is realistic. He says he's pain-free, but Spicer wonders whether that's the bravado of an ex-Marine talking.

"I'm afraid for him," Spicer says. "I don't want him to suffer. Both my parents … I watched them painfully get out of this world [with cancer]. I hope he doesn't have any of that."

If they keep busy, maybe they won't have to think about it, the 800-pound clock ticking in the room.

Spicer comes by once a week, sits on the floor and goes over a stack of requests with Harwell. A lady they've never met wrote a list of her 12 relatives she wants Harwell to say hello to in heaven. Thousands of people want autographs. The phone rang nonstop until Spicer suggested the couple get an unpublished number.

The Harwells live in a nursing home in Novi. There are 900 inmates here, Harwell jokes. And constant reminders of a man's mortality. Spicer lugs the giant card to his Jaguar, and when he steps off the elevator, he passes by a framed photo on the table. It's of a resident who recently died.

"Honestly," Spicer says, "I don't even like to think about him not being alive."

The kid

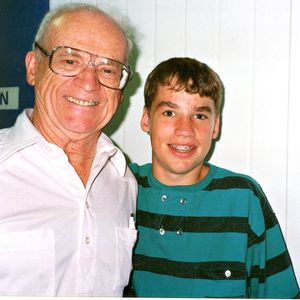

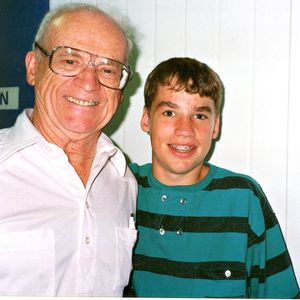

Courtesy Tony Hawley

Harwell and Tony Hawley outside the booth at Tiger Stadium in 1991.

How do you say goodbye to a man who's been in your ear for your entire life? Like most Michigan boys, Tony Hawley spent every summer with Ernie Harwell. He'd run an extension cord through his neighbors' backyards so the kids could listen while they played baseball. He'd sneak a Walkman into school just to hear Ernie's voice on Opening Day.

Hawley was 13 in December 1990 when it was announced that Harwell's contract wasn't being renewed by the Tigers, sparking widespread outrage throughout the state. The boy from Belding, Mich., had to do something. So he sat down and wrote him a three-page letter.

If you ever need a job or any money … even if you need anything like an organ or a kidney, you can call me.A few days later, the phone rang at Hawley's house. It was Harwell.

It was like getting a call from the president, Hawley says, and they became unlikely friends, separated by 60 years. Hawley wrote Harwell three or four times a week about his junior varsity baseball team and his desire to get into the broadcasting business. He knows now what a pain he must've been. But Ernie read every letter.

Harwell left for California to do Angels broadcasts part time for a year in 1992, but it wasn't the same. When Mike Ilitch bought the Tigers in '93, one of his first moves was to hire back Harwell.

"In my opinion, Ernie is the No. 1 sports celebrity in the state," says Ilitch, who rarely does interviews but replied through a spokeswoman. "He means so much to the fans. … For many, it's a tie to their childhood, their youth, their home."

Twenty years, hundreds of letters, and the kid who offered to give up his organs and his allowance eventually grew up and became a radio man. Hawley currently runs five stations in San Antonio and still keeps in touch with Harwell.

They talked after the diagnosis, and Harwell assured him he was fine and everything would be all right. It's just like him, Hawley says. He wants to make everybody feel comfortable, just as they did on long summer afternoons when Harwell eased into his chair and let the sounds of the ballpark take over his microphone.

"The reason I ended up doing this is because of him," Hawley says.

"He was inspiring, and it wasn't just because he was so gracious and nice. He was a good coach."

The singerSusan Feliciano is scrambling. It's four days before Christmas, and the wife of the man who sang "Feliz Navidad" has a million things to do. But mention the name Ernie Harwell, and the family will drop everything and come to the phone to chat.

"Ernie is a doll," Susan says.

Their story goes back to 1968, when the Tigers were in the World Series. The club was looking for someone to sing "The Star-Spangled Banner," and Harwell suggested an up-and-coming Puerto Rican talent who had a hit rendition of "Light My Fire" zooming up the charts.

The musicians at the stadium knew something was amiss when they asked for a key and Jose said he'd play the background music on his acoustic guitar. He delivered a slow, Latin-jazzy, emotional version of the song at what apparently was the wrong time, the heart of the Vietnam War and months after the assassinations of Martin Luther King Jr. and Robert Kennedy.

It caused a national ruckus. Middle-aged men were throwing their shoes at the television. Fans were calling Feliciano a Communist.

"[Ernie] almost lost his job because of me," Feliciano says. "Any time you [did] something different in this country, you were accused of being a Communist."

Susan was a 14-year-old Tigers fan living in Michigan at the time, watching the game at home, appalled by the way fans were treating Jose. She tried to start a Feliciano fan club but didn't hear back from anyone for nine months. Her mother came up with an idea: Why not ask Ernie Harwell to help?

The men had become friends over the anthem fiasco, and Harwell put Susan in touch with Feliciano. When Susan was 18, she met Jose. They fell in love and eventually had three children. She still tells her kids today that they're here because of Ernie.

Regardless of what the doctors say, Jose Feliciano still believes Harwell is going to keep going.

"They say it's inoperable, but that's only doctor's slang," he says. "Nothing is impossible with God."

Vintage Ernie Harwell

• Ernie Harwell was inducted into the Radio Hall of Fame in 1988. Listen to him on the Hall of Fame's Web site.

• Harwell wrote a poem in 1955 called "The Game for All America," and read it at his 1981 induction to the Baseball Hall of Fame. Click here to see him read a portion of his poem.

----------------------------

The catcherFor 10 uncertain days,

Jim Price leaned on Harwell. Price is a former Tigers catcher, a longtime friend in the booth, and he was diagnosed with cancer in his kidney last month. It was one of the largest masses doctors had ever seen. Price, a private man, was worried.

Harwell called every day and asked Spicer and former Tigers great Alan Trammell to pull over when they were driving to say a group prayer while Price sat on the other line. Shortly after that, doctors were able to contain the cancer in his kidney. Price believes it happened because Ernie has a direct link to God.

"Here's a man in the condition he's in doing these things for little ol' me," he says. "He's worried about me."

Back in the day, when Price was a catcher in the late '60s and early '70s, players went out of their way to be on Harwell's pregame show. They looked forward to talking to him. He was part of the team. He laughed at his own jokes, made fun of himself and always stayed out of the way. Harwell used to chuckle at the broadcasters who'd boast that they "put 'em in the stands today." No voice, he'd say, is ever bigger than the game.

But some faithful listeners might disagree. One night in Detroit, Price, Al Kaline and Harwell were sitting in a large, noisy restaurant. Price and Kaline chattted away, and Harwell sat back and listened. When he finally chimed in and his voice carried through the joint, the place got quiet.

"Everybody leaned in to listen," Price says. "It was kind of like that E. F. Hutton commercial."

The requestJust about everybody who meets Harwell, even if it's just for a quick minute, immediately considers him a close friend. Maybe it's his Southern hospitality, growing up as a paperboy for the Atlanta Georgian, that made him so personable. Until the past few months, Harwell could never say no.

He was at U.S. Cellular Field in Chicago about eight years ago, hunkered in the booth on a rainy night, wrapping up one of 50,000 goodnights in an empty stadium. It was a long day, it was cold, and Harwell just wanted to retreat to the team hotel. Then a voice emanated from the lower regions of the stadium.

"Ernie! Ernie! Can I have your autograph?"

The elevators were shut down; the jaunt, through roped-off seats and slippery steps, would be beyond treacherous for a man well into his 80s.

Harwell poked his head out of the booth and waved to the stranger.

"OK," he said. "I'll be down."

The firefighterIt is said in Michigan that the sound of Harwell's voice makes men think of their fathers. A couple of years ago, Kevin McNutt lost his father and grandpa -- loyal Harwell listeners -- within the span of a few months. He thought about them and what fans could do for Ernie. So he launched a Facebook page in the hope of adding Harwell's name to Comerica Park.

The cause currently has 36,000 backers.

McNutt, a Grandville, Mich., firefighter, has contacted the Tigers about it, but he's conflicted. He knows Harwell balks at the idea of any kind of attention. He doesn't want to put any added burden on him.

McNutt wonders whether Tigers fans got spoiled. They had Ernie for so many years that they got used to him always being around and never thought about the end. McNutt would listen to him at the pool, in his grandpa's basement, at Belle Isle Park, watching the freighters roll across the Detroit River into Canada.

He loved how Harwell personalized his broadcasts. He'd say a foul ball was just caught by a fan in the fourth row from Monroe. It made it seem as if he knew everyone in the stadium. Home runs were the best, McNutt says.

It's long gone!

The biggest supporterThere's an old joke that Lulu Harwell might be responsible for the only man on this planet who ever disliked Harwell.

When the couple were in college in Georgia, Lulu was dating a boy who was a fraternity brother of Ernie's. He introduced them at a dance, and then Lulu, smitten with Ernie, dumped the other guy and asked Harwell to the next gathering. She was from Kentucky; he was from Atlanta. Neither knew then that first glances would melt into 68 years.

Elizabeth Merrill/ESPN.com

Lulu and Ernie Harwell at their home in Novi, Mich.

"That's when she was a hillbilly," Ernie says, laughing, and then shifts into more politically correct-speak. "Now she's … what do we call it, Appalachian American."

They had four kids together and still occasionally finish each other's sentences. He makes her breakfast; she sleeps in when he gets up at 6 a.m. to do his exercises. Want to see how much fight Harwell has left in him? Watch him exercise. He drops to the floor and does sit-ups and stomach crunches. He swings his arms back and forth in a workout he calls a whirling dervish.

Until about four months ago, he jumped rope 300 times a day. Now, with his balance a little off-kilter, he runs in place 300 times. He hasn't thought about quitting the exercises now that he's dying. "You can't skip," he says. The nurse tells him if he keeps it up, it might ward off some of the pains that come along. It might help him last a little longer.

It's obvious he wants to stay longer for Lulu. He calls her his biggest supporter. She puts up with him daily, he says, and will be beside him until the inevitable.

"He never missed a game," Lulu says, emphasizing the long and healthy life he's enjoyed. She's had Ernie to herself for seven years now -- he officially retired in 2002 -- but in some ways, she's always shared him. They open packages filled with bread and cakes and quilts.

They listen to goodbyes but rarely shed tears.

"I have great faith that heaven's there and I'll see my brothers and my mom and dad when I get there," Harwell says. "I think it's better than here. I think God always has the best for us.

"I just have faith. It's just there. It's not any big deal."

Elizabeth Merrill is a senior writer for ESPN.com. She can be reached at merrill2323@hotmail.com.

Courtesy Tony Hawley

Courtesy Tony Hawley

Elizabeth Merrill/ESPN.com

Elizabeth Merrill/ESPN.com